In the analytic tradition, one popular characterisation of philosophy has been that it is conceptual analysis. After the Quinean attack on the analytic-synthetic distinction, this view has become less popular, but it still has its adherents. The idea is that philosophers take a problem (e.g. free will) and then decompose it into a set of pertinent concepts (e.g. responsibility, determinism, freedom, agency), clarify what these concepts might mean and how they relate to each other, and thereby hope to remove the air of mystery which hangs over the unanalysed problem. Ordinarily, at most, such a philosopher might recommend we use a word in a different way (e.g. talking of ‘free agents’ but not ‘free actions’ or vice versa), or stop invoking certain concepts at all (e.g. final causes). But there is another less conservative model of philosophy which also takes its object to be concepts, most often associated with recent continental thought.

Deleuze thinks philosophy is the “continuous creation of concepts.” (WIP: 8.) In part, this is meant to align philosophy more with productive activities, which make and create, than those that test and observe — philosophy is to be more poesis than theoria. Deleuze brings his own inflections to the notion of the concept, and thereby philosophy as concept creation too. But the details of Deleuze are not my concern here. Instead of criticism of Deleuze, my focus here is the kind of uses (or misuses) to which this idea of philosophy as concept-creation has been put.

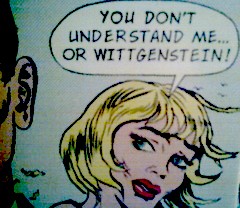

The main ill-effect of the idea of philosophy as concept-creation which I want to point to here has been its reinforcement of one way of approaching philosophers. So, we get the philosopher-as-conceptual-toolsmith model. At its worst, we end up with synecdoche run amok, where one prominent idea comes to dominate everything else about a philosopher’s work — Wittgenstein = language games, Foucault = power-knowledge, Levinas = the Other, Badiou = the Event, etc. For example, Simon Critchley describes the post-Kantian landscape thus:

you get the Subject in Fichte, Spirit in Hegel, art in the early Schelling, and then in later nineteenth and early twentieth century German philosophy, Will to Power in Nietzsche, Praxis in Marx and Being in Heidegger. (New British philosophy: 187)

Similarly, Graham Harman claims that Heidegger only really had one idea which he endlessly repeats, namely the tool-analysis. But even without this extreme hermeneutic reductionism, there is a real coarsening which can go on when we chisel down a philosopher to a handful of headline concepts.

All of this is not to say that philosophers do not produce new concepts. Nor is a plea for endless textual analysis and scholarly ensconcement such that we never put a philosopher’s ideas to work in a new context. And neither does it display a blindness to the realities of communicating philosophical ideas in circumstances where people do not have the time or inclination to master more than the headline ideas of many thinkers. Instead, all I want to do is make the observation that emphasising the concept-creation model of philosophy too much can promote some dubious tendencies in both historiography and contemporary critical debate.

Firstly, unsurprisingly, it often leads to trading in caricatures and straw men. Second, it tends to drive a mechanical style of philosophy, whereby the aim is to ‘apply’ the concepts of the master-philosopher to a given material rather than approach it afresh — ‘I will now give a Foucauldian/Wittgensteinian/SR analysis of x’. Third, it tends to occlude the historical dimension of much philosophy (responding to a certain set of material circumstances; intervening in a historically evolving tradition). Fourth, it can also shroud what is valuable in philosophical work, which sometimes is the purchase which a new concept provides, but is often dissolving a bogus problem, reframing a question to allow it to be answered, effecting a more diffuse change of perspective on an issue, instilling a sense of Entfremdung with respect to something we’ve taken for granted, and so on. All these dangers make me wary of overplaying the image of the philosopher as a forge for concepts.

You make some very good points. It seems that the important point is to recognise that philosophy has two different dimensions: a critical one and a constructive one. One cannot just create new concepts, one must carefully maintain and adjust the ones we already have (including those produced by our philosophical forefathers). Perhaps the engineer is a better analog than the artist here.

Maybe I should amend my Deleuzian slogan to “more techne than theoria“. That seems to capture the type of productivity involved a little better.

First, this is an excellent post. I’ve noticed this tendency as well, but never thought about it as an issue that ought to be philosophically problematized. And in a way I think this exact mode of „problematization“ is a much better way to think about philosophy, rather than the production-of-concepts model. This mode of problematization seems to involve a kind of reordering of things, such that the philosopher’s perspective provide a special insight, a special perspective, that unveils what was once hidden and in fact renders it obvious (usually I’ll say to myself, „At the time, I wouldn’t never thought about it like that, but now in retrospect it appears totally obvious“).

If we think about philosophy from this perspective, as a totalizing (and not necessarily in a bad sense) reorientation of the world, I think the role of concept-production or concept-expansion are epiphenomenal. They assist in making this new world discernible. To this extent, philosophers would not be reducible to their conceptual „greatest hit,“ but should be thought specifically in relation to how they go about reorganizing things, which concepts provide a clue towards grasping.

Thanks.

I like the way you put things here; it chimes with the ‘aesthetic’ model of philosophy which I’ve had a go at characterising before (in the post ‘Philosophy as Bildung’ linked above the comments). To put it crudely, the most productive form for philosophy is something like ‘Look at it this way’ rather than ‘This is how it must be’. I think it’s in this sort of spirit that Wittgenstein says that he could imagine a work of philosophy made up entirely of jokes. The point being that philosophy should issue in a shift of perspective more so than assent to a novel proposition.

Pingback: The Intial “Brilliant” Exaggeration: Mongering Brilliance « Frames /sing

Wonderful post. I love the braiding between Wittgenstein claims to clarity and Continental creativity.

One thinks back to Descartes and imagines him sitting there in his study saying to himself, “How can I be original…how can I be original…how can I be original…ah, the world is made of two Substances, this will live forever” instead of facing the difficulties of having come up with a mechanistic natural philosophy with a firm desire to describe the world accurately, yet a philosophy facing the problem that the Catholic transubstantiation of the Bread of the Eucharist retained no place, the threat of the Inquisition hanging over his work.

p.s. It should be pointed out that Harman thinks, or at times has thought, that even when Heidegger departs from his ONE idea, he is only confused and doesn’t realize what he is thinking.

I haven’t read Tool Being (only a few of Harman’s papers on Heidegger) and don’t know that much Heidegger, but even though I am not in the best position to judge, I tend to think Harman just can’t be right about Heidegger. In a way, he is fighting the good fight by trying to dispell the heavy portentous air that surrounds Heidegger. But you don’t have to buy into some reverential attitude concerning the profound depth of Heidegger’s thought to think that this reading streamlines Heidegger unhelpfully much. As I say, though, I’m not really in a position to mount a defence of this specific claim, since I don’t know either of them in enough detail yet.

I agree that Harman is fighting the Good Fight against the portentous air, and I even applaud his innovative simplification, as it allows one to cut through much of the terminology and alternation, but it is when Harman makes the next step and feels that he has seized the very core truth from Heidegger’s grasp itself, and made it his own, we are stepping into strange land.

The bigger issues I think are those you raise, that of philosophical clarity, strawmen building, master making. If you look closely at any philosopher you enjoy you realize that the ONE idea that was supposed to characterize his (her) thought really doesn’t do justice to what he (she) was trying to say. Wittgenstein is not MERELY saying that language use is like game playing, and Nietzsche is not JUST talking about Will to Power (in fact some scholars suggest that he isn’t talking about Will to Power at all). It seems that Harman’s reductive literalism strongly misses the point of any of these conceptual positionings.

Well said. I think another danger with the idea of the philosopher as producer of concepts is that it leads to a view that more concepts = better concepts. Rorty sometimes seems to think this way: all the philosopher really does is produce more discourse, more conversation. But what we do with the concepts matters a lot more than the concepts themselves, even – or especially – if we’re just working with concepts others have already created. It’s tremendously difficult to think well philosophically in clear prose that doesn’t involve neologisms, but if one can do it, one will have some very thankful readers.

I think you’re right about Rorty and his ‘continuing the conversation’ trope. When he explicitly discusses the role of concepts (such as in his critique of McDowell), he does much the same thing, decrying the idea that there is such a thing as a bogus concept.

I think that Rorty is right to attach importance to that we continue communicating, fashioning new perspectives and vocabularies, and producing novel redescriptions of ourselves and our world. But foremost is what we end up saying, whether we get more insight into a situation, whether a new perspective opens up new practical possibilities, and so on. Communicating just ‘for the sake of it’ is not always a bad idea, but heeding Rorty you’d form the impression that it doesn’t really matter what philosophers end up saying, just so long as its novel and it keeps people happy.

hi Tom,

Great post. With regard to “dissolving a bogus problem,” I think that’s the type of philosophy I’ve liked best for a long time. I don’t have an argument for this move, it’s mostly just a matter of taste. This is not meant as a rhetorical question – can you think of recent continental examples of this? It may just the limits of what I read, but I can’t think of any.

cheers,

Nate

No recent continental figures spring to mind as advocates of the therapeutic approach. Karatani in Transcritique (his excellent book on Kant and Marx) comes close in places. Zizek (who incidentally takes up Karatani’s notion of parallax, albeit without great success) has been saying in the past few years that it is not the philosopher’s job to answer questions but to scrutinise how we pose them, revealing how we perceive a problem can be itself a major part of the problem. This has a therapeutic ring to it, though it’s not clear that Zizek’s own work actually manages to carry out this project that well — though he is great for those occasional ‘I never thought of it that way’ moments!

Tom [on Rorty]: “Communicating just ‘for the sake of it’ is not always a bad idea, but heeding Rorty you’d form the impression that it doesn’t really matter what philosophers end up saying, just so long as its novel and it keeps people happy.”

Kvond: Does this for you include the late accomodation he made towards Davidson’s claim of the necessity for a Theory of Truth? I’m not sure that this is the case.

I was thinking of his big-picture conception of the role of philosophy, elaborated in his last papers (collected as ‘Philosophy as Cultural Politics’).

Do you feel that Rorty thought that metaphysical philosophy, taken seriously, (as long at it made people happy) is something he would advocate?

He seems to have taken a firm position on the kinds of concepts we should be pursuing. Perhaps I am misunderstanding you. I’m not sure that Rorty is that far from Wittgenstein when talking about good and bad philosophical projects.

In short, I think he would. Of course, he thinks that there are numerous reasons why it is bound to fail in any such endeavour — it ends up being authoritarian, inhibits democratic discussion, it doesn’t make sense, and so on. So, he thinks that ‘metaphysical philosophy’ cannot contribute much to the project of social progress, and so the liberal ends of making people happy. But his conception of the role of philosophy in general is a kind of boiled-down Deweyan one in which the philospoher’s role is to advance the social good. And again, this social good is something that Rorty sees in deflated liberal terms, namely securing conditions for people to pursue lives that make them happy, or more accurately, allow them to avoid suffering.

This is odd to me because the first half of the answer seems to contradict the latter half of the answer. I mean, if metaphysical pursuits end up producing “authoritarianism”, then advocating metaphysical pursuits in the name of the “social good” or conditions that make people happy is pretty silly.

To put it simply:

1. Pursuing non-human authority leads to unhappy, less free people.

2. People can pursue non-human authority if it makes them happy and more free.

That was precisely my point. Rorty can say that philosophies are only ultimately valuable insofar as they contribute to the social good, claim that if metaphysical philosophy did so it would be worthwhile, but deny it does so.

We are getting there.

So how to this jibe with the idea that the MORE philosophical concepts we have the better…it doesn’t matter WHICH philosophical concepts the better?

Obviously if philosophy was loaded with concepts which exclusively were of the metaphysical variety there very number would do nothing to redeem them in Rorty’s eyes.

Sorry I wrote that wrong…

We are getting there.

So how does this jibe with the idea that the MORE philosophical concepts we have, the better…it doesn’t matter WHICH philosophical concepts they are, we just want more of them?

Obviously if philosophy was loaded with concepts which exclusively were of the metaphysical variety their very number would do nothing to redeem them in Rorty’s eyes.

And how is this different than Wittgenstein’s own therapeutic vision of philosophy? Rorty’s entire point, I thought, was to dethrone philosophy as a master discourse of a sorts. It would seem pretty clear that all concepts designed by philosopher to reestablish it as a master discourse would be concepts Rorty would object to as not only useless, but also somewhat damaging (at least historically so).

To give an example Tom, from the book you just emailed me (thank you). Justice as a Larger Loyalty, when Rorty says,

“So we have to drop the Kantian idea that the moral law starts off pure but is always in danger of being contaminated by irrational feelings that introduce arbitrary discriminations among persons. We have to substitute the Hegelian-Marxist idea that the so-called moral law is, at best, a handy abbreviation for a concrete web of social practices” (47)

How do you fit this into your thought:

“…but heeding Rorty you’d form the impression that it doesn’t really matter what philosophers end up saying, just so long as its novel and it keeps people happy”

Are you just saying “It DOES matter what philosophers are saying, because some of the things that they say DON’T keep people happy, but as long as they avoid certain concepts (like the Kantian ones mentioned above) then indeed it doesn’t matter what philosopher’s say and think, as long as it is novel and keeps people happy?”

The discussion of concepts here might have complicated things, because they come up in a few different senses in Rorty’s work. For example, he thinks there are no empirical concepts which are illegitimate through lacking perceptual content, but that’s a different discussion from the sense of concepts with respect to philosophy as concept-creation. So, I’ll adopt a different vocabularly here.

The main issue is Rorty’s idea that philosophers should be in business to “continue the conversation of the West” (as he puts it at the end of Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature), which Plato began, but without addressing the metaphysical topics which Rorty thinks structure Plato’s own position.

Why continue this ‘conversation of the West’? I think Rorty comes to emphasise what he takes to be a Deweyan role of philosophy, as an interlocutor but but not an overseer in the project of social progress. Here, it doesn’t matter so much whether people like what philosophers say (they can be ‘gadflies’), but whether it ultimately helps to provide us with new perspectives, loosen old certainties, suggest new aspirations, and so on, in a way that enriches our cultural discourse. And this is meant to be a good thing insofar as it helps us live our lives as citizens of democratic polities, through all the subtle but far-reaching ways having a reflective, pluralistic and open-minded populace might seem to.

The problem which I have with all this is not that I want to defend the traditional problems of epistemology or metaphysics (far from it) or I think that philosophy shouldn’t have a kind of modest world-historical role. Instead, I think Rorty overlooks the sort of constraints which arise within this ‘Conversation’ itself. He thinks we ought to change the conversational topic when we suspect it is no longer socially useful to keep talking (e.g. he wants to ignore the problems of Cartesian epistemology, and talk about something more interesting).

However, I think Putnam and McDowell are right here that we ought not be so hasty. So, (with Putnam) I think there are philosophical responsibilities to be discharged here, even when we suspect a philosophical problem is somehow bogus or idle, and (with McDowell) I think that we had better diagnose these bogus problems at their root lest they spring up in a new form — a kind of philosophical ‘return of the repressed.’ Furthermore, I don’t take the social or democratic function of philosophy to be its primary aim (though as should be clear from the rest of the blog I think it can be ‘socially useful’ in all sorts of ways, such as how we think about ethics or the natural sciences, etc.)

Tom: “I think Rorty overlooks the sort of constraints which arise within this ‘Conversation’ itself. He thinks we ought to change the conversational topic when we suspect it is no longer socially useful to keep talking (e.g. he wants to ignore the problems of Cartesian epistemology, and talk about something more interesting).”

Kvond: And how to do you separate this change of topic out from the “concept clarity” notion of Wittgenstein’s, which I thought you already were invoking against Continental “creativity”?

Rorty and Wittgentein seem to be on the same page on this.

I don’t think they are on the same page on this one. (Incidentally, this is one of the main reasons that I became far less enamoured with Rorty than I had once been.) Wittgenstein famously wants to “show the fly the way out of the fly-bottle.” In other words, he tries to carefully retrace the steps that have led philosophers into confusion, often in meticulous detail and with great psychological acuity. But Rorty (quoting Conant here) rejects this kind of diagnostic approach: “‘Rorty’s recommendation appears to be that one should leave the fly in the fly-bottle and get on with something more interesting.’ Conant here gets me exactly right.”

So, I think Rorty admires Wittgenstein’s recognition that philosphers are often saddled with a lot of junk problems which we can ditch, but he does not think we need to engage in the extensive sort of diagnostics that Wittgenstein recommends. As I like to put it, it’s like Rorty is a psychoanalyst who is content to tell their patients that he is sure that their problems are the result of deep psycho-social traumas stemming form their formative years, but who does not then feel the need to work through all their specific problems with them. I wrote this post a little while back on some of this stuff.

I guess we read Rorty differently. When you say, “Wittgenstein famously wants to “show the fly the way out of the fly-bottle.”…“‘Rorty’s recommendation appears to be that one should leave the fly in the fly-bottle and get on with something more interesting.’ Conant here gets me exactly right.”

I see Rorty as absorbing all of Wittgenstein’s anti-metaphysical proviso’s but not thinking much about arguing endlessly with those who STILL think the fly is on the bottle. He wants much less to heal other philosophers from their own illnesses. In fact this is much nicer than the stronger normative Wittgensteinian therapy. He is not at all like a psychotherapist, of the two. Frankly, he was the much more “adjusted” thinker. Wittgenstein wanted to heal philosophy/philosophers because he was healing himself. Rorty is much more concerned with the place of philosophy within society, which seems to be the way it should be.

I would want to ask, where do you find Davidson on this question of “concepts” and their plethora/creation? To me Rorty pretty much ends up agreeing with everything Davidson has to say.

The point of undertaking a more diagnostic approach to traditional philosophical problems is not (necessarily) to continue arguing with those who still take there to be a genuine problem here (though it might end up putting oneself in a better position to do so). Instead, it is to better understand why the problem seemed compelling, why it held such a grip on us, from whence it came and so hopefully how we can avoid iterations or similar problems cropping up again.

One of the reasons that this is valuable is that ‘traditional philosophical problems’ are not only problems which are met by philosophers who go looking for them. For example, sociologists, computer scientists and everyday people can all inherit the problems surrounding Cartesian dualism; and it is helpful to have something helpful to say to them beyond “don’t sweat it” even if we agree that the problems are somehow bogus. Furthermore, there are specific problems which I think Rorty himself faces through failing to trace traditional epistemological problems back to their roots, such as his handling of nature and its relation to reason. (Again, as Putnam and McDowell deftly show, each in their own way.)

On Davidson and concepts, as I’ve said, this might not be the best way to frame these issues because of the different roles for conceptuality already in play, as well as the vocbaulary gap between Deleuzians and the post-analytic types. That said, I think we’re better off asking how Rorty and Davidson see the role of philosophy. In some ways, they seem to be disarmingly similar (as evidenced in that video interview between them I posted a while back). Rorty has been prone to say more connecting philosophy and social hope (to borrow the title of one of his books) than Davidson; and Davidson has been prone to place more emphasis on the helpfulness of semantics and the constitutive ideal of rationality in understanding the human situation. But they remain pretty similar. Neither are quite as zealous as the Deleuzian in forging new sets of concepts, but they go someway in this direction insofar as they seem to think that we just have to get on the task of coming up with new descriptions of ourselves that pass the muster of our peers, where we cannot appeal to truth as a goal of inquiry.

Tom: “The point of undertaking a more diagnostic approach to traditional philosophical problems is not (necessarily) to continue arguing with those who still take there to be a genuine problem here (though it might end up putting oneself in a better position to do so). Instead, it is to better understand why the problem seemed compelling, why it held such a grip on us, from whence it came and so hopefully how we can avoid iterations or similar problems cropping up again.”

Kvond: And for Rorty this is vestigal, in a sense, the appeal to the non-human. It is not solely do to a conceptual confusion which is working merely like something of an optical illusion.

Tom: “For example, sociologists, computer scientists and everyday people can all inherit the problems surrounding Cartesian dualism; and it is helpful to have something helpful to say to them beyond “don’t sweat it”.

Kvond: And there is a tendency to oversell the pervasiveness of Cartesian Dualism. In fact if you look very closely at Descartes there is some likelihood that Descartes did not really hold a typically Cartesian conception (as it later to be summarized).

Tom: “That said, I think we’re better off asking how Rorty and Davidson see the role of philosophy. In some ways, they seem to be disarmingly similar (as evidence in that video interview between them I posted a while back). Rorty has been prone to say more connecting philosophy and social hope (to borrow the title of one of his books) than Davidson; and Davidson has been prone to place more emphasis on the helpfulness of semantics and the constitutive ideal of rationality in understanding the human situation. But they remain pretty similar.”

Kvond: I can’t say that from this description that either of them are on the side of “let’s just let philosophy make up as many concepts as possible, and it doesn’t matter which one’s they are, as long as there are a lot of them”. In fact I’m not sure how such a thought could be offered in Davidson’s direction, but you do seem to try…

Tom: “Neither are quite as zealous as the Deleuzian in forging new sets of concepts, but they go someway in this direction insofar as they seem to think that we just have to get on the task of coming up with new descriptions of

ourselves that pass the muster of our peers, where we cannot appeal to truth as a goal of inquiry.”

Kvond: Hmmm. So perhaps we are getting to the core of this. Philosophy needs a “goal”, which must be “truth”. I assume you mean Truth capital “T”. It is not enough for philosophy to have a theory of truth (small t), as Davidson offers. Instead it must have a Capital T truth. But how ever do you reconsile this, again, with Wittgenstein, who you seem to favor? In fact from your description of Rorty and Davidson, both of whom were highly influenced by Wittgenstein, I see nothing in Wittgenstein that adds the dimension of a goal of Truth? Quite the opposite.

Sorry to press you on this, but you seem to be straddling two sides (or more) of a fence. Rorty is bad because he is not therapeutic to philosophy, like Wittgenstein, and he should be aimed at the “goal of truth”, instead of advocating a sheer numericity value of “concepts”. I understand that you don’t like Rorty (and Davidson?), but I can’t see how your criticism of each over “truth” fits in with your praise of Wittgenstein.

Perhaps its not worth straightening me out on this, these are just my questions.

I’ll address your comments in order, though I think you’re starting to grasp at straws.

I’m not sure what you mean here. For one, adopting a therapeutic approach need not imply any special relation to the non-human. There is no implication of realism, whether robust or modest, nor anything transcendent. Looking for the origins of a problem can be a matter of sifting through linguistic, cultural and philosophical assumptions and habits to see how a problem struck us as gripping but impossible to untangle; and that is what therapeutic philosophers usually do. No controversial non-human authority appears.

Neither point is really relevant. Yes, people do often try to indict more-or-less all the problems of the modern world to lingering Cartesianism. But saying that there are some problems with a residual Cartesian mindset which afflict non-philosophers does not involve buying into any anti-Cartesian witch-hunt, and nor does it suppose they are difficulties that are even that widespread. It simply stands as a solitary example. Secondly, there are, as always, interpretative questions here. But again they are not relevant to the point at hand. Plato was no platonist, but that doesn’t prevent people correctly talking of Platonism as a worldview. Rorty effectively recognises as much through his reply to McDowell in the Rorty and His Critics volume.

I have not claimed that either of them do this, and I have repeatedly emphasised that the language of ‘concepts’ tends to be misleading in this particular context (as opposed to discussing the Deleuzian view). Instead, I have reframed this in terms of Rorty’s well-known trope of ‘continuing the conversation.’ The closest thing to the view you have outlined is perhaps Amod’s original comment, but he still does not say this, only that Rorty tends to think that more concepts (in the sense of ways at looking at things) will lead to better concepts (a better way of looking, by Rorty’s measures). So, again, this is another non-starter.

None of this follows from what I have said. I merely mentioned in passing the main normative constraints on inquiry Rorty and Davidson recognise, namely our peers. Famously, they deny that truth is a goal of inquiry, since they think that we cannot tell when our individual beliefs are true, and since goals must be recognisable, truth cannot be a goal. So, they think we can only have more readily graspable normative standards, such as what our peers make of our beliefs and projects, as epistemic guides to inquiry. Alongside many others sympathetic to their position, I happen to think they are wrong about this and that we can make sense of truth, in the modest sense which they recognise is achievable, as a possible goal of inquiry. But this does not introduce some mysterious higher sense of truth. Nor still does it suppose this is what philosophy must be after.

I have already indicated where Rorty begins to depart from Wittgenstein over questions of philosophical methodology. Naturally, this does not mean that Wittgenstein and Rorty (or Davidson) do not share a great deal else.

I have a number of disagreements with Rorty and Davidson’s positions, but on most issues, and in the grand scheme of things, our views are fairly close. There’s lots of valuable stuff in both of their work, and I have no axe to grind here, just what I take to be good-natured disagreements with them.

Thanks for the lengthy response. You are right that many of these issues are secondary, but I missed the part where Wittgenstein adopts the “goal of truth” aim for philosophy, apparently an important goal. Where do you see this?

To begin by re-iterating my own position, I’ve no tubthumping desire to place truth at the centre of philosophy any more than it features in any other sort of inquiry.

I haven’t claimed that Wittgenstein does see truth as a goal of philosophy, because it would be potentially misleading to put it that way. Given his views on the tasks of philosophy, there would be a danger in this way of talking, insofar as it can suggest that philosophy is after a set of explanatory theories. But in another sense, as long as we take care here, it would be quite innocuous to claim that Wittgenstein thinks that truth features as a goal for philosophy, since he takes philosophy to be a matter of providing ‘descriptions for particular purposes.’ Careful descriptions fashion us with a set of trivial truths, and these act as ‘reminders’ which we are prone to forget when in the grips of a philosophical problem. Reminidng us of these ordinary truths, which we have a practical grasp of in everyday life, becomes the mainstay of philosophy for Wittgenstein. This can take many forms, whether constructing perspicious representations of some area of language, asking us to imagine what we might say in novel scenarios, and so on. But mapping, mastering and deploying these truths, in response to specific philosophical problems, is what Wittgenstein thinks philosophy should be in the business of doing.

Does this mean that Wittgenstein thinks ‘truth is a goal for philosophy’? As Wittgenstein himself puts it, it doesn’t matter what we say, just so long as we know what we mean. Getting a grip on Wittgenstein’s position is what matters; labels come after.

No obscure sense of truth (transcendent, metaphysical, extra-human, or whatever) comes into play here. I am sure Rorty and Davidson would have no real problem with this; their critique of truth as a goal of inquiry has a somewhat different character, relating to what epistemic standards we can appeal to in inquiry. For them, truth cannot be a norm that gives us substantive guidance — it cannot feature as that sort of goal; but that need not preclude the sort of Wittgensteinian methodology outlined above. They just think that there are other, more useful, things for philosophers to do.

Tom: “But in another sense, as long as we take care here, it would be quite innocuous to claim that Wittgenstein thinks that truth features as a goal for philosophy, since he takes philosophy to be a matter of providing ‘descriptions for particular purposes.’”

Kvond: And how would this differ, for you, from Davidson’s “descriptions”? You seem to have toe-stubbing difficulty with Davidson’s relationship to truth, but seem quite embracing of Wittgenstein’s relationship to truth. You seem invested in having Davidson on one side of the fence (probably because Rorty agrees with much of Davidson, if not all), and Wittgenstein on the other side. But I can’t picture just how each side is supposed to relate to the “goal of truth”. Wittgenstein indeed addressed himself to “specific philosophical problems” just as Davidson did. It seems more like you want to play “good guys” and “bad guys”.

But perhaps the biggest point is the question, Is the world a better place – or, if that kind of question isn’t allowed – Is philosophy better off if it had tons of McDowells and Putnams, universities churning out these kinds of thinkers across the planet? Or would it be better off if it were producing Putnams, Rortys, Davidsons, Derridas, Deleuzes, Habermases, DeLandas and Badious, Dennetts, Searles, etc.?

For my part I would cringe if it were only producing Putnams and McDowells, as focusedly interesting as these two might be. What a sterile thought world. I think that this is what Rorty has in mind with the conversation of the West.

I responded to your post though in saying that Graham Harman isn’t really doing philosophy with his Great Exaggeration theory, largely this is because he isn’t really answering entrenched problems, but rather seems to be trying to shoot straight to the genius part. But I would prefer a philosophical West or World that included a variety of invented concepts designed to answer entrenched conceptual problems, and would probably prefer that dreams of a purely therapeutic, “Truth as goal”, correction to all thought program to form only one branch of a greatly diversified tree.

You’ve begun to fixate on the phrase ‘truth as a goal’ for some reason. Originally, I mentioned this in passing as a feature of Rorty and Davidson’s general conception of inquiry, not as some great flashpoint with respect to how they do philosophy. I’ve already said that Rorty and Davidson would find much of my characterisation of Wittgenstein’s methodology innocuous, so I don’t know why you see me as trying to set up great dividing lines on this particular issue. There are some differences between Rorty, Davidson and Wittgenstein on philosophical methodology — they just don’t have that much to do with how any of them understand truth or the general epistemic constraints on all inquiries. Rorty and Davidson are less focused on the idea of philosophical therapy than some other Wittgensteinian thinkers; this is hardly controversial or a crude attempt to set up ‘good guys’ and ‘bad guys’. I have set out some of the reasons why I think we should embrace a more therapeutic idea of philosophy, but this not because I think that people like Rorty and Davidson don’t care about truth.

Secondly, just because I prefer Putnam and McDowell et al on these methodological issues doesn’t mean that I think everyone else is worthless. It’s perfectly possible to be a pluralist about what universities should be teaching whilst thinking that certain approaches are more produtive than others.

I think we’re getting into diminishing returns territory now, so I think I’ll break off my responses here.

Tom: “…just because I prefer Putnam and McDowell et al on these methodological issues doesn’t mean that I think everyone else is worthless. It’s perfectly possible to be a pluralist about what universities should be teaching whilst thinking that certain approaches are more produtive than others.”

Kvond: This makes me chuckle, for you seem to have come full circle to Rorty’s position. The more concepts the better, but some are better than others.

Tom, a lot of this is on stuff I haven’t read for years or haven’t read at all, but/so it’s been an edifying read. I just wanted to say, I thought this was succinct and true: “I don’t take the social or democratic function of philosophy to be its primary aim.” Thanks as well for the earlier reply re: the relative lack of therapeutic approaches in continental philosophy. On that, insofar as I get you and Kvond’s back and forth…. I remember Rorty saying somewhere something to the effect that the right approach to certain mistakes was not to explain or argue against them, but to mock them. That’s correct I think, but the details of where to take this approach matter a great deal and I’m sympathetic to your saying basically “Rorty wants to leave too many flies to die in their flybottles, instead of letting them out or at least trying to understand how they got in there.” I wonder if there’s some tie here to this element in Rorty and to his eventual turn toward some continental figures, if there’s a link to this turn and a shift in Rorty’s orientation away from therapeutic philosophy (flybottle-uncorking-philosophy). Maybe not. Anyway, all of this thought provoking reading, so thanks again.

warmly,

Nate